Our DEI History

Welcoming Youth From Every Quarter

With the founding directive in its 1778 constitution to educate “youth from every quarter,” Phillips Academy has embraced a notion of diversity as a core part of its mission. Over time the school’s definition of diversity—how it interprets “every quarter”—has evolved and generally broadened in response to a changing nation and world. Andover has met these demands by regularly responding to societal needs and shifts, and asking the essential question: How do we uphold our ideal to be a “private school with a public purpose”?

From the days when Harriet Beecher Stowe hosted anti-slavery meetings with Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth on campus in the 19th century to the dedication of the Richard T. Greener Quad in 2018, named after Phillips Academy’s first African American graduate who also became Harvard’s first African American graduate, Andover has, to widely varying degrees, provided African American students access to its extraordinary education. Probably the first serious discussions about racial diversity at the school occurred during the tenure of Alfred E. Stearns, who was Principal from 1903 to 1933.

From the early 1890s until about 1910, there was a small but steady flow of usually one African American student per class. Early in his tenure, Stearns was relatively supportive of these boys’ presence at Andover, but he later reconsidered that support. In a 1913 letter to the President of Howard University on another topic, he showed no hesitancy in providing an explanation for his opposition to having African American boys at the school:

My chief reason for taking this position has been the fact that the majority of these boys have seemingly lost their appreciation of the proper relation of things, and have been turning away from the splendid opportunities offered them to work among their own people, to attempt the impossible among people of another race. [Youth from Every Quarter by Frederick Allis]

He reached out to “the best informed man [he] could find,” Hollis B. Frissell, a white alumnus who was the Principal of historically Black Hampton Institute in Virginia. Frissell affirmed Stearns’s belief that the school was “harming more than helping the colored boys.” Stearns then reached out to Booker T. Washington, at the time among the most powerful African Americans in the country and President of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, who was reportedly even more strongly opposed to admitting African American boys to PA. As a result, from 1910 until the 1930s when Stearns’s tenure ended, only one African American boy graduated from PA, Benner C. Turner ’23, who went on to Harvard College1 and then to Harvard Law School and ultimately served as President of historically Black South Carolina State College in the 1960s.

In total, between its founding and the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling outlawing segregation in public schools, more than 30 African American boys attended Andover, while a number of peer institutions, including Abbot Academy, did not graduate their first African American students until the 1950s or later.

The history of DEI efforts at Abbot prior to its merger with Phillips in 1973 was not exemplary. After its founding in 1828, the first African American girls did not graduate from Abbot until 1955 primarily due to resistance by Southern white families and some trustees who were especially concerned that admission of African American girls might lead to their daughters being exposed to African American boys, which was unthinkable to these families.

As late as the 1940s, African American boys at PA were clearly not welcome to events on the Abbot campus, a practice that was endorsed by Headmaster Claude Fuess. Abbot admitted Asian girls as early as the 1940s. When a powerful, long-serving white trustee who had strongly opposed admission of African American students died in 1950, Abbot Principal Marguerite Hearsey began efforts to admit the first Black students. When the admission of the first girls was announced, three white families withdrew their daughters.

Beth Chandler, from Atlanta, and Sheryl Wormley, from Washington, D.C., both girls from prominent, highly educated African American families, entered the school in 1953 and graduated in 1955. Of note, Chandler’s grandfather, a Jamaican immigrant, was for many years the lead gardener for the campus of PA. By the early 1970s, there were only 10 African American girls at Abbot out of about 400 students, and the school created a space for an Afro-American Center.

Abbot also participated in an Intercultural Exchange program with Dakota Sioux girls from the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, although the exchange was difficult for both sets of girls. While open to becoming more diverse as the country gradually progressed, Abbot struggled to make the girls feel truly welcome and comfortable.

In contrast to the passive acceptance of a small number of African American boys for much of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Andover more actively reached out to students from Asia, welcoming Japanese student Joseph Hardy Neesima who was the first Asian student to graduate in 1868. From then until the end of the century, several Asian boys attended the school each year. Beginning in 1878, Andover launched the Chinese Educational Mission (1878-1882) and was a leader in opening its doors to Chinese students in the early 1900s with close to 100 Chinese boys entering between 1903 and 1920.

Addressing the Gap

Although Andover’s commitment to racial and ethnic diversity varied over its first 170+ years, the number of African American students began to slowly and steadily increase in the 1950s. In 1963 representatives from more than 20 independent schools convened on Andover Hill to consider ways to recruit “talented Negro boys” to independent schools so that they would be better prepared for a college education.

The Independent School Talent Search eventually launched A Better Chance

(ABC). That program continues to be an important resource for identifying and recruiting students of color to independent schools. Andover’s list of ABC

alumni is distinguished and includes the first person of color to serve as a charter

member of the Board of Trustees.

Af-Lat-Am @ 50 Celebration in 2018

Af-Lat-Am @ 50 Celebration in 2018

The achievements of ABC, no doubt, inspired the 1967 Faculty Steering Committee on the Composition of the Student Body to recommend that Andover increase the representation of underserved boys over a five-year period. With successful onboarding through summer transition programs—and an innovative admission and financial aid staff—Andover made its first significant strides to expand its racial diversity. This effort resulted in an increase in the number of Black students from 15 in 1963 to 54 by the end of the decade.

While the increase represented progress, there were no formal support structures to support the boys. With a nation in racial unrest, many Black students were inspired by the Civil Rights Movement. In 1968, they formed Andover’s African American Student Association to support students and create a strong sense of Black culture and community. As Andover enrolled a growing number of Latino students, the organization further expanded its mission and in 1974 changed its name to the Afro-Latino-American Society. Today, Af-Lat-Am thrives as the longest standing cultural club on campus.

Being Intentional

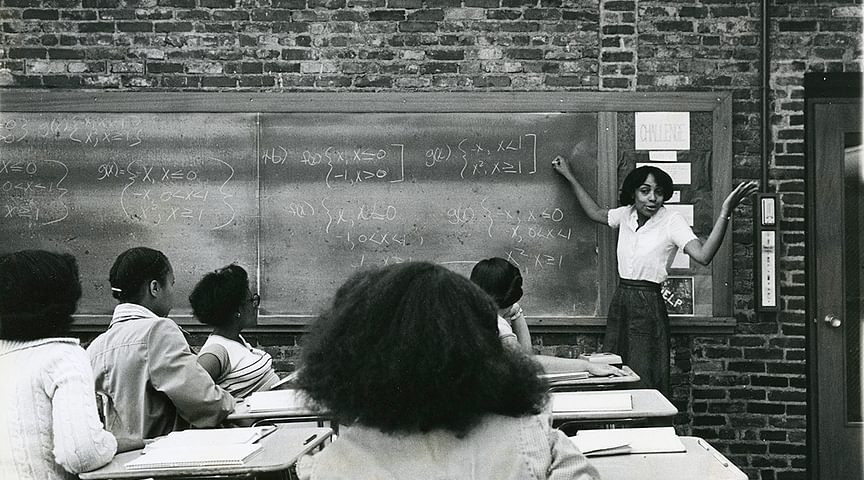

The 1970s brought the merger with Abbot Academy, making Phillips Academy a coeducational institution. In 1977, Phillips Academy created its

first outreach program, Mathematics and Science for Minority Students. Now known

as (MS)2, the program was founded to strengthen educational opportunities for underserved public school students. (MS)2 continues to offer outstanding

summer enrichment for underrepresented students of color from across the

country by advancing their STEM skills and increasing their opportunities to

enter the most selective colleges and universities.

(MS)2 Instructor Diane Jones teaching in the summer of 1978

Building Support

As the 1980s approached, Andover expanded its efforts toward diversity by

again welcoming students from China. The Dean of Admission traveled to China

in June 1980 to build a partnership with the Harbin Institute of Technology.

Andover enrolled its first Chinese exchange students later that fall. The Harbin

exchange program lasted 20 years and paved the way for other secondary schools

to welcome students from China. Today, Andover’s connections to China are

expansive. Additionally, students come from many Asian countries including

South Korea, Japan, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, and Vietnam.

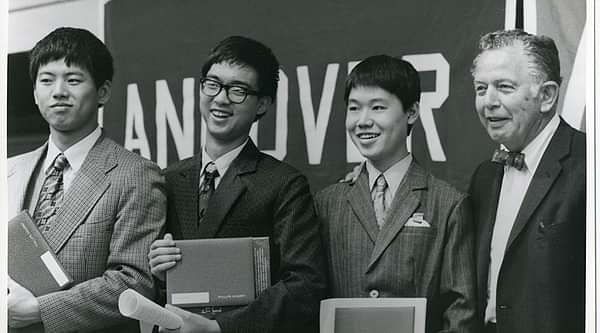

Dean of Admission Joshua Miner with Harbin students (1981-1982).

Dean of Admission Joshua Miner with Harbin students (1981-1982).

At this point, little is known about Andover’s early efforts to recruit students from other parts of the world now represented by significant numbers of students from areas such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Africa. A short-term goal is to expand understanding of the school’s history of recruitment and admission from other parts of the world.

In 1986, Andover hired its first Director of Minority Recruitment in admission. PA expanded recruitment efforts to include gifted and talented programs in urban centers, like Baltimore, Brooklyn, Atlanta, and Los Angeles. Programs like Prep for Prep and the Oliver Scholars Program in NYC also helped to significantly expand representation of Black and Latinx students. This increase brought demand for enhanced support structures on campus. In a letter to Headmaster Don McNemar in 1985, students requested that the school hire a Minority Counselor to help them navigate the complexities of an elite New England boarding school. Students wrote, “The faculty is ignorant of many of the cultural, psychological and emotional challenges peculiar to minority students, and are ill-equipped to help and understand us.” This prompted McNemar to appoint the school’s first “Minority Counselor.” The role expanded to become the Dean of Community Affairs and Multicultural Development (CAMD) in 1990.

At the same time, the number of African and Latin American students arriving on campus and the representation of Asian and international students began to sharply increase. Under McNemar’s leadership, CAMD established the first series of anti-racism workshops on campus. Over the course of four years, the Academy required all faculty members to attend an intensive workshop focused on developing their cultural competency skills with the goal of the school becoming an anti-racist community. During this time, many student activists were motivated to raise campus awareness of issues of race. A student protest in the winter of 1989 urged the school to cancel classes on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day in acknowledgement of the recently decreed national holiday.

In January of 1990, Phillips Academy did, in fact, cancel classes for the first time to recognize and honor the legacy of Dr. King. Students and faculty spent the day on campus attending workshops on a broad range of social justice issues or participated in community service programs in nearby Lawrence. Today, MLK, Jr. Day continues to be devoted to raising awareness and educating the community on current topics related to diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice. Most notably, staff are now a part of the campus celebration.

Under McNemar’s leadership, the faculty became meaningfully more diverse. It is believed that the first faculty of color were African American and joined the faculty in the late 1960s or early 1970s.

In 1993, the CAMD office moved to Morse Hall in the center of campus and became a hub for multicultural programming and a support center for students of color, international, and LGBTQ students. Several positions were created to meet the needs of the community during this era: International Student Coordinator, Advisor to Asian and Asian American Students, Advisor to LGBTQ issues, Advisor to Latino Students, Advisor to Black Students, and Assistant Dean of CAMD. Affirming the school mission to educate youth from every quarter: The CAMD office was created to raise awareness and encourage understanding of difference of race, gender, ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic class, geographical origin, and sexual orientation. Today, the office sponsors workshops, lectures, and educational programs, and it supports nearly 30 affinity groups and cultural clubs as well as the CAMD Scholar Program. The annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Day program, now in its 31st year, remains a hallmark of CAMD.

Applying A Critical Lens

In 1999, the school commissioned the Richard T. Greener Study to review and assess the experience of Black and Latino students and alumni. The goal of the study was to determine what helps students perform at their best and to understand how the Andover experience has contributed to success for Black and Latino alumni. The school soon followed with a similar study for Asian students. Again, students echoed the need for increased representation of faculty of color as well as the need for culturally competent counselors, teachers, and coaches. There was also a strong desire to increase peer-to-peer mentorship and involve the trustees in the development of enhanced supports for students of color.

Also in 1999, the Addison Gallery of American Art showcased To Conserve a Legacy: American Art from Historically Black Colleges and Universities, a collaboration with the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Williamstown Regional Conservation Lab. The project showcased art from the collections of six historically Black colleges and universities and included conservation of art from their collections as well as internships for HBCU students. Since its founding in 1931 as a campus and community resource, the Addison has had a record of increasing attention to acquiring and exhibiting art from across our country’s racial and ethnic communities. A notable example was Pekupatikut Innuat Akunikana/Pictures Woke the People Up: An Innu Project with Wendy Ewald and Eric Gottesman (2012), an indoor exhibition, campus wide outdoor banner installation, and artists’ residency, including Ewald, Gottesman, and 11 members from teenagers to elders of the Innu community. The project explored the representation of the Innu people of Labrador and the cultural, economic, social, and environmental challenges they have faced in the wake of forced settlement in the 1960s.

Under the leadership of Head of School Barbara Landis Chase, Andover’s commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion guided the 2004 Strategic Plan:

“At the heart of this strategic plan is a reaffirmation of the school’s historic and distinctive mission...to educate ‘youth from every quarter.’ Our goal reflects the components necessary to accomplish this task in the 21st century.”

With a focus on ensuring access to an Andover education, along with academic and personal success of all students, regardless of economic status, Andover adopted a need-blind admission policy in 2008. At the same time, the school created academic enrichment programs including the ACE (Accelerate, Challenge, and Empower) summer program, to address individual preparation gaps primarily in math, and expanded the Academic Skills Center. Additionally, the development of the Global Perspectives Group led to what became the Learning in the World (LITW) program in 2014. LITW gives every student the opportunity to study off campus and experience a different culture.

To respond to the demographic shifts of the Andover student population—by

2011, 44 percent of students were receiving financial aid—Chase commissioned

the Access to Success Working Group (A2S). The charge of the committee was to

ensure that all students have every opportunity to find success at Andover. The

timely work of this committee helped to bridge the leadership transition from the

14th to the 15th head of school.

Expanding the Effort Academy-Wide

In 2013, Head of School John Palfrey received the A2S report. The principal recommendation was to replace the cluster “Academic Review” process with a holistic “Student Review”. The creation of an electronic communications system allowed a student’s “team” of faculty to receive timely updates and expedite a plan for their academic and personal success. In addition, a summer “Transition Program” was created for full scholarship students who might benefit from additional time to prepare for the rigorous PA academic program. And, most notably, the committee recommended that the Academy enhance efforts to develop the cultural competency of both students and adults to promote an environment that is more inclusive, inviting, and equitable. While Andover had committed many resources to diversity and access, the A2S Working Group revealed gaps in the community’s knowledge of essential skills needed to create a viable learning environment for an increasingly diverse student body.

After 30 months of community dialogue, increased professional development—centered on understanding issues related to race and socioeconomics—as well as increased data collection guided by the Assistant Head for Enrollment, Research, and Planning, the priorities of the 2014 Strategic Plan were carved. Connecting Our Strengths: The Andover Endeavor “set forth a vision to redefine excellence for our contemporary school by reinterpreting Phillips Academy’s foundational values in a fresh and inspiring way.” Equity and Inclusion; Empathy and Balance; and Creativity and Innovation became the pillars of the strategic plan.

Centering equity and inclusion warranted the creation of a new position, and Linda Carter Griffith moved from Dean of CAMD to become one of the nation’s first Assistant Heads for Equity and Inclusion, establishing Andover as a model for other independent schools to soon follow. In 2017, following an external review of the Rebecca M. Sykes Wellness Center, Griffith’s portfolio expanded to include medical and counseling services. This move signaled an institutional belief that in order for students to thrive at Andover, each student would need to be healthy and have a strong sense of belonging in the community.

The institution acted swiftly to implement the priorities of the 2014 Strategic Plan, which included an increase in the hiring and retention of faculty of color. There were notable increases in both Asian and Latinx identifying colleagues, which mirrored increases in those student populations.

The Interdisciplinary Studies Department was launched in 2017 and charged with “embedding race, class, gender, and sexual orientation into the curriculum.” A goal of the strategic plan was to “nurture the academic and personal growth of all students as they navigate a complex, intentionally diverse learning community.”

In the fall of 2016, the Board of Trustees participated in diversity training under the leadership of Board President Peter Currie ’74. Following the session, the Board voted to create the inaugural Equity and Inclusion Committee, and Gary Lee ’74 was named chair. This decision affirmed Andover’s commitment to living its values.

In 2018, the institution reaffirmed its commitment to its mission of educating youth from every quarter by amending its Statement of Purpose to also include PA’s community values.

In September 2018, as noted earlier in this section, the school formally

honored its first African American graduate, Richard T. Greener 1865, with the naming of the Greener Quad. Inspired by an anonymous donor, Andover

recognized the importance of symbolism and representation in bringing to life

key aspects of the school’s history. Greener’s name now marks the space where

the school’s most important ceremonies are held, including Commencement and

the Head of School Investiture.

The Richard T. Greener Quadrangle Dedication Ceremony

In this same year, Andover conducted its first Climate and Culture Assessment, which fulfilled an institutional directive of the 2014 Strategic Plan— to perform “regular assessments of equity and inclusion on campus, considering the interests of all students, staff, faculty, and administrators.” Survey results revealed that while the demographics of the Academy had changed significantly from its founding, the lived experiences of many students, staff, and faculty unfortunately continued to reflect the deeply rooted and persistent racial and ethnic inequality in our nation today.

In another example of student-led progress, Native Americans of Phillips Academy (NAPA) was founded in the winter of 2019. The organization was created to build a stronger community for people often left out of the historical narrative, and to provide a space that celebrates and affirms Indigenous identities. On MLK, Jr. Day 2020, about 25 students held a silent, peaceful protest outside of the chapel demanding that the school acknowledge that it resides on Native American land. In November 2021, the Board of Trustees adopted an official Land Acknowledgement.

Furthermore, the Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology has been a leader in repatriation since the passage of the Native American Graves Protection & Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990. The Act—considered both property law and civil rights law—requires museums to identify ancestral remains and sensitive cultural objects and return them to the appropriate tribal nations. In the 1990s, the Peabody was involved in the repatriation of nearly 2,000 ancestors excavated from Pecos Pueblo in New Mexico, the largest repatriation to date. Many other significant repatriations have followed, including work with the Wabanaki tribes in Maine, the Wampanoag in Massachusetts, and tribal nations in the Southwest.

Inspired by the racial reckoning of the summer of 2020, the school launched the AATF—amidst a global pandemic—because Andover is a community that aspires to always do and be better.