December 06, 2021

Schmear This!

An old family recipe helped Rebecca Schrage ’97 put New York-style bagels on the map in Hong Kongby Rita Savard

Every recipe tells a story. For Rebecca Schrage, a marriage of two worlds, family tradition, and new frontiers is where the plot thickens. So it’s fitting that, of all things, a food in the shape of a circle takes center stage in her kitchen.

Bagels, like pizza and mom’s mac and cheese, are one of those hot-button foods that evoke strong feelings. Schrage’s earliest memories involve waking up on Sundays to the heady scent, distinctively doughy and slightly sweet.

“We’d rush downstairs in our pajamas to dig in,” she says. “Weekends at the Schrage house were for bagel brunches with schmears [a generous slathering of cream cheese] and all the fixings—lox, whitefish salad, egg salad, and chopped liver.”

The golden-brown circle, perfectly imperfect, would still be warm as she raised it to her mouth and closed her eyes. This is where her journey began.

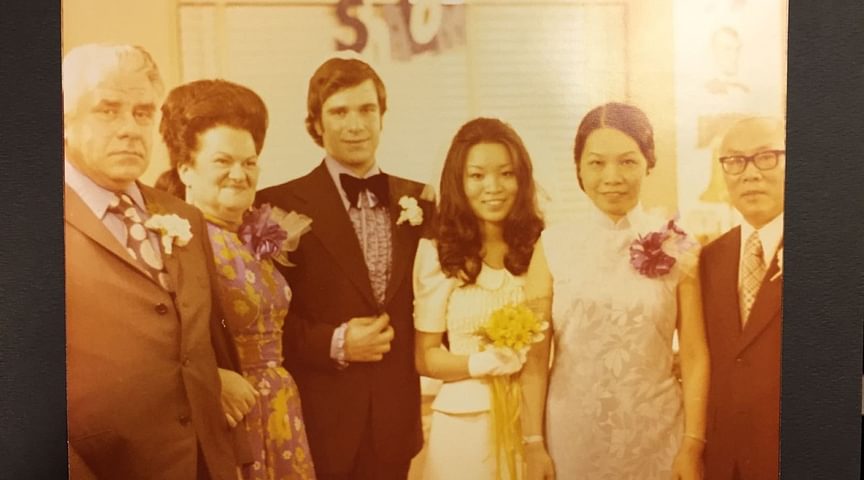

Food was the language of love for Schrage’s mother, Elizabeth, who found joy immersing her family in cuisine from two different worlds—Hong Kong, the place of her own roots, and the Jewish food traditions of her husband, Michael.

Schrage’s grandfather, Benjamin Schrage, emigrated from Poland to New York City, where, history confirms, the Polish-Jewish community introduced the unique and tasty bread to America. Benjamin owned and ran New York delis throughout the 1950s and 1960s. His granddaughter, who lived in New York post college when working on Wall Street as an investment banker, is—like any New Yorker—fiercely particular about the bagel. The art of boiling the dough, she says, and the persistence of a technique passed down through hundreds of years separates the real deal bagels from the phonies.

“A great bagel is all about the chew,” Schrage declares. “A thin, shiny, crackly crust and a dense, chewy interior come from the proper boiling. If it’s not boiled, it’s not a bagel. Steaming doesn’t count.” Of course, she adds, the "secret sauce" combination of mixing, moulding, timing, and boiling is not as simple as following a recipe.

You need to really feel the dough and adjust for the conditions—like extreme humidity here in Hong Kong. The hand rolling is an art that must be learned. You don't want to overwork the dough, or else you won't get that perfect bagel texture. From beginning to end, a bagel takes up to 48 hours.

”Schrage earned a degree in economics and Asian studies from the University of Pennsylvania. Her investment banking career took her from New York to New Zealand to Hong Kong. There, she joined fellow expats in a chorus of "can’t-find-a-decent-bagel-in-Hong Kong.” The closest thing Schrage found were frozen, colorless, flat bagels—a sure sign that the dough had been rolled out by machine instead of by hand.

There was only one way to ensure a fresh, authentic bagel in Hong Kong: Schrage dusted off her grandfather’s recipe and made her own.

A lucky friend who got to try one of Schrage’s first batches of homemade bagels requested three dozen for a birthday party. Schrage obliged.

Serendipitously, the party was attended by people from Hong Kong’s food industry, and immediately after Schrage got a call from a well-known chef who just had to have some. More requests followed. Schrage purchased an extra oven and refrigerator and was soon rising before dawn to fulfill orders for restaurants, hotels, corporate events, and individuals—all before heading to her day job.

In 2014, CNN Money ran the story “Hong Kong’s Bagel Banker,” and seemingly overnight Schrage’s purpose changed. She found a commercial kitchen and decided to go all in.

“The fact that there were no real bagels in Hong Kong was shocking,” Schrage says. “It’s a melting pot of so many different cultures that appreciate high-quality food. That first order I got from a top restaurant chef was key—it made me realize there was an opportunity for a real wholesale business out here.”

For top hotels, she began to hand roll to order. The Mandarin Oriental preferred larger sesame and poppy seed bagels, Grand Hyatt wanted mini bagels, and The Peninsula wanted pink beetroot canapé bagels for their iconic afternoon tea.

“Whatever they wanted, we did,” Schrage says. “The coolest part was that many of our wholesale partners called the bagels ‘Schragels’ on their menu, which helped us expand really quickly.”

The media caught on, with stories in the New York Times and South China Morning Post. And in 2016, the global magazine Jetsetter named Schragels one of the top bagels in the world.

Schrage now runs a wholesale factory and a thriving retail space.

In the Schrage family, the bagel represents the perfect food. A circle. No beginning or end but held within a single delicious ring—echoes of hard work, good intentions, the soul of a grandfather, and a gift of nourishment to the people it feeds.

“I’ve always believed in the dream,” says Schrage.

Other Stories

PA's alumni magazine acknowledged for excellence in design and writing