February 09, 2018

Back… to the Future

Designer Jake Barton ’90 builds meaningful connections between history and new generationsby Rita Savard

Time is moving backward in Jake Barton’s fast-paced Manhattan office—back to London’s Roman era in 240 AD, back to the site of a slave warehouse in Montgomery, Ala., circa 1877, and back to the Franklin School in Washington, D.C., where Alexander Graham Bell transmitted his first photophone message in 1880.

By diving deep into stories of the past and merging them with present-day technology, Barton’s Local Projects, an architecture and media design firm, is building meaningful connections between history and new generations.

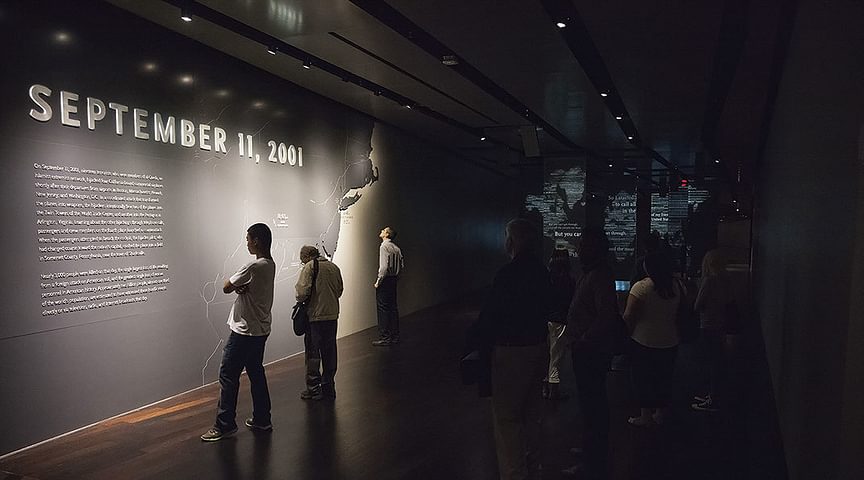

Barton launched Local Projects in 2002. Four years later, his budding startup with a total of three employees was tapped to codesign the 9/11 Memorial Museum, a very personal and challenging project for the native New Yorker. But then again, the human story is always at the heart of Barton’s high-tech world.

On September 11, 2001, Barton and his wife, Jenny, were back in New York City, having returned from their honeymoon just two days prior.

“At first, I heard it on the radio,” says Barton, who didn’t own a TV at the time. “We went to a laundromat around the corner that had a television and watched the tower fall. I wanted to be closer to understand what was going on, so I convinced my wife to ride our bikes downtown. She wouldn’t go farther than Soho, but it was very intense. As we got farther south, we saw more and more people covered in white ash. You could see the death cloud that was still settling on the horizon. That day’s trauma really affected everything.”

Barton began grad school and started Local Projects soon after.

Obsessed with the idea of collaborative storytelling, “where groups of people would share their stories and tell a larger, more diverse, and more inclusive narrative,” and understanding the Internet would be the medium to connect everyone together, Barton quickly carved out a name for Local Projects when the company helped develop StoryCorps in 2003. The idea was relatively simple: set up a soundproof booth inside New York’s Grand Central Station and encourage passersby to record a narrative of personal history. Their unique stories were then archived by the Library of Congress. The nonprofit project has since become a popular NPR radio broadcast, has won multiple Peabody awards, and represents the single largest collection of human voices ever gathered.

For the 9/11 Memorial Museum, Barton proposed a similar strategy—take the personal stories of people affected and use them to educate and engage.

Over the course of eight years, Barton and his small team worked on the original master plan and all the design, and then produced the media. The result is an emotional journey that connects visitors through voices and visuals of those who died, as well as survivors who witnessed the events.

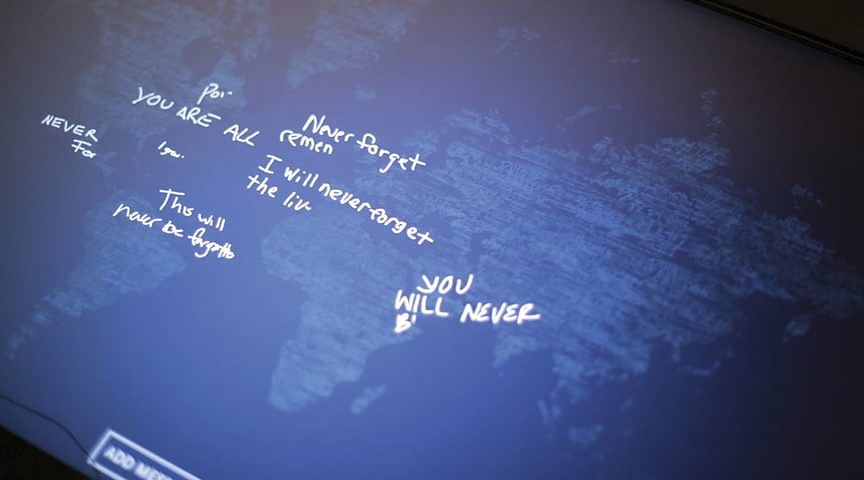

One of the museum’s most challenging exhibits to design was the mammoth “Timescape,” which is curated by an algorithm that tracks and combs through millions of daily news articles and pulls key terms related to 9/11. The headlines, projected onto a 100-foot-wide granite wall, chart the global impact of 9/11 in real time.

Two Andover alumni who died in the attack, Todd Isaac ’90 and Stacey Sanders ’94, are included in the museum’s narrative.

The museum today still feels like a chamber of memories where people can share their stories and listen to other people’s stories. It still invites a sense of community-building within those stories of witness and response.

”Each unique project that Barton and his creative team tackles has a similar mission: building exhibits designed to endure the test of time. That’s why, he stresses, they have to affect people emotionally.

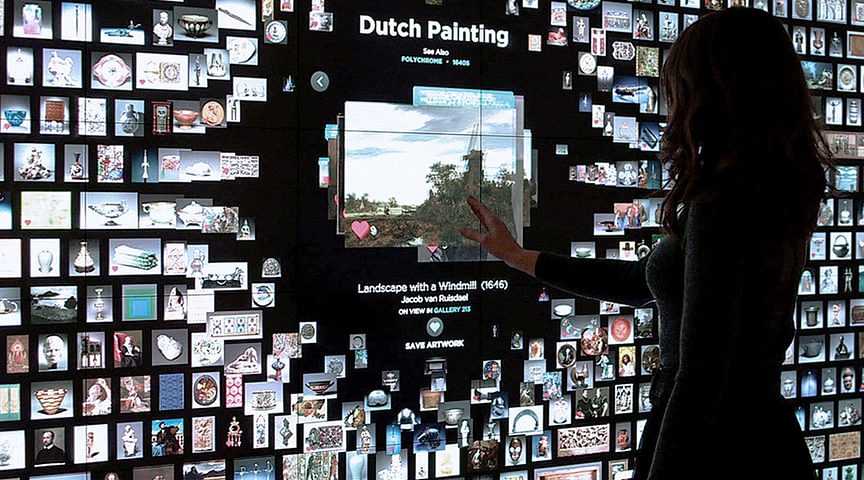

That end goal is evidenced in the sound of laughter welling up through the halls of New York's Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum—one of Barton’s personal favorites. Here, each visitor is given a special pen and invited to actually draw on the walls, creating live wallpaper.

“It seems to unleash constant joy, and that makes me super happy,” Barton says.

Whether their work invokes play or serious contemplation, at Local Projects, narrative is a time machine and memory is the fuel. The company’s interactive exhibits and digital storytelling experiences are changing the way museums engage with the public across the United States and all over the world.

Across the pond, Local Projects helped breathe new life into the London Mithraeum, a reconstructed Roman-era temple built in 240 AD as a tribute to a mysterious god called Mithras “The Bull-Slayer.” The mithraeum was discovered by accident in the aftermath of World War II, during excavations of rubble on London’s Victoria Street in 1954. The remains of the temple were haphazardly reassembled at another location. But when business news outlet Bloomberg acquired the original site in 2010 to house its European headquarters, the company also took responsibility for returning the mithraeum to its rightful home. Since the museum opened in November 2017, approximately 600 visitors a day have descended about 22 feet below the Bloomberg building into a dimly lit cave where ancient ruins and a multimedia experience transports them back 2,000 years.

Another museum opening this April tapped Local Projects to help create an intense and provocative experience which, says Barton, aims to change the way we think about race in America. Through the nonprofit organization Equal Justice Initiative, The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration was built on a site in Montgomery, Ala., where enslaved people were once warehoused. The museum, just steps away from a dock and rail station where tens of thousands were trafficked during the 19th century, will also incorporate holographic images, 800 six-foot monuments acknowledging thousands of lynching victims, and sculptures dramatizing the legacy of slavery to tell a story of mass murder and racial terror in the U.S.

“The work we do is constantly motivated by finding a deeper meaning,” Barton explains. “If we can create something that sparks thought, conversation, emotion—that might play a role in helping to elevate humanity—I believe that’s the real reward.”

In the winter of 2019, Local Projects will turn back the clock again to give the public a whole new perspective on the history of language. Planet Word, a free museum of linguistics set inside the historic Franklin School in Washington, D.C., will use high tech to inspire a love of language in all its forms. The landmark site, where telephone inventor Alexander Graham Bell had his first big telecommunications breakthrough in 1880, will be a place to explore speech, literature, journalism, and poetry through unique, immersive learning experiences.

Today, Barton’s company employs 70 people. Time travel agrees with them. Stepping off the elevator to Local Projects’ eighth-floor offices, visitors are greeted with one word in bold black type: Yes.

“Design, innovation, and invention are all about saying yes to new ideas, unexpected connections, and intuitive convictions,” Barton says. “We’re always looking to build something that lasts for generations, and the key to that is actually not to rely on technology. If you install something that tells a good story, that changes people’s thoughts on a topic and engages them in a deeper, meaningful way—that’s what endures.”

Other Stories

PA's alumni magazine acknowledged for excellence in design and writing