May 09, 2022

The comeback coach

Terrell Ivory ’00 beats the odds and is back on the courtby Nora Princiotti ’12

After a horrific car accident, Terrell Ivory ’00 was given a 5% chance of recovering. This is a story of community, connection, and a miraculous comeback.

In the early morning hours of July 27, 2019, Terrell Ivory ’00 was driving north on Main Street, the bell tower in sight. He has no memory of what happened next.

The PA admissions officer and boys’ varsity basketball coach had returned from a three-week trip to China only two days before and had not been especially kind to his body as he adjusted to the 13-hour time difference.

“I should have just slept,” Ivory says.

Instead, he pushed himself to stay awake, thinking he would reacclimate faster. His first day home, Ivory went running twice. The next day, he didn’t want to miss a dinner with incoming students in the ACE summer program. Ivory had takeout delivered to the admissions center and gathered with that group, eagerly getting to know new faces. In the throes of exhaustion, Ivory would later end up falling asleep behind the wheel, losing control of his car, and crashing into a tree on the front lawn of a town selectman. His airbag deployed, but his head still hit the steering wheel, causing his brain to swell and bleed.

Ivory laid unconscious for about an hour before a passing police officer discovered him and called an ambulance. Doctors at Lawrence General Hospital immediately recognized that Ivory needed emergency brain surgery at a neurotrauma center. He was airlifted to Tufts Medical Center in Boston, where a neurosurgeon performed a craniotomy, removing half of Ivory’s skull flap to relieve pressure from his swelling brain. He was then placed in a medically induced coma. Once Ivory was stable, the doctors searched his belongings and found his Phillips Academy ID.

A WINDING BLUE ROAD

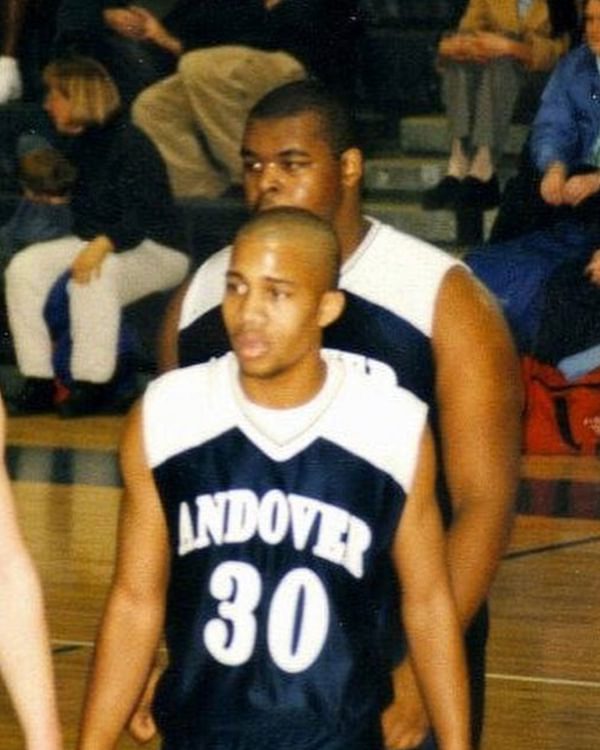

Ivory ’00 as a post-graduate in 2000.

Ivory ’00 as a post-graduate in 2000.

Much of Ivory’s life has been spent on campus. His family discovered Andover when his older brother, Titus, was thinking about next steps after high school in their hometown of Charlotte, North Carolina. Titus was a football and basketball star with college offers, but his mother, Carlenia, wanted to make sure his academics were as good as his athletics. A family friend suggested looking into a postgraduate year at Andover. Ms. Ivory did some research that connected her with local alumni admissions representative Joe McGirt ’63, who invited her and her sons over to talk about the school.

“The more they learned, the more excited they became,” McGirt recalls. “Terrell was younger, but I remember remarking about what a great kid he was and that he had the qualities the admissions folks tell me to always look for—someone who is academically focused and really a nice person, a kind person.”

Titus spent a postgraduate (PG) year at Andover, graduated in 1996, and went on to Penn State. He had a great experience at Andover, which sold his little brother and, perhaps more importantly, his mother.

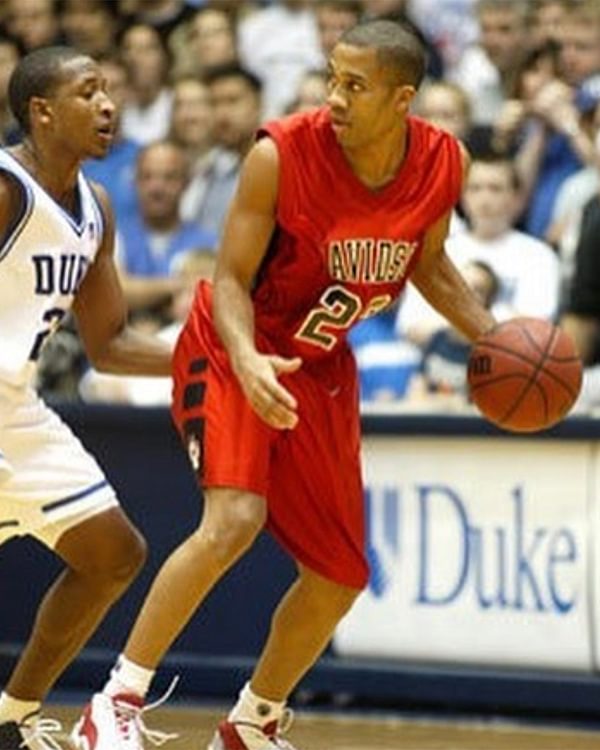

Ivory ’00 played collegiately at Davidson, and served as director of basketball operations at Davidson.

Ivory ’00 played collegiately at Davidson, and served as director of basketball operations at Davidson.

Three years later, Terrell came to Andover as a PG and then went on to Davidson College, where he played basketball. After playing professionally in England, he returned to the United States and coached at Blair Academy in New Jersey and served as director of basketball operations at Davidson before joining the coaching staff at Colgate University.

Ivory was moving up in the coaching ranks at Colgate but missed the close connections he’d felt in a boarding school environment. He even considered a coaching position at Deerfield. However, Leon “Coach Mo” Modeste, Andover’s athletics director at the time, had designs on bringing Ivory back to Andover. In 2012, Ivory went to work at PA.

Today, in addition to maintaining his coaching duties, Ivory is the associate director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Outreach, an associate director of admissions, and a house counselor in Stearns House. He is known for sitting in the front row of every faculty meeting and volunteering readily (including to coach JV tennis). Ivory is also a frequent spectator at fellow admissions officer and varsity baseball coach Kevin Graber’s practices and games.

ANDOVER MEANS FAMILY FOR LIFE

The person from Tufts who called the PA Campus Safety number on Ivory’s ID card likely had no idea the community they were mobilizing. Knowing only that Ivory had been in an accident and was hospitalized, the Campus Safety officer contacted Athletics Director Lisa Joel, who quickly headed to the hospital. Joel called Graber and some of Ivory’s other close colleagues. She also called Carlenia Ivory and promised to stay by her son’s side until family could get there. Joel recalls explaining to the nurses at Tufts why a rather large group of co-workers—none related to the patient—should be allowed into Ivory’s ICU room. “‘We’re a family,’ we told them,” Joel says. And it worked.

Ivory was on a ventilator. Half his skull was off his head. Joel, Graber, and a rotating cast of Andover colleagues stayed by his side. They held his hands and talked to him, played videos of Ivory and his daughter, Leia, singing together, and reminded him just how much he had to live for.

When Ms. Ivory learned about the accident, one of the first things she did was call Joe McGirt. They’d become close friends, and she knew that his son, Matt McGirt ’94, was a doctor who’d recently reconnected with Terrell when he started looking at Andover for his own children. The elder McGirt said he’d have his son call her. On the phone, Ms. Ivory told Dr. McGirt that Terrell had been in a bad accident and was at Tufts but that she was struggling to get any other information. McGirt offered to call and see if his fluency with hospital phone systems could get him to a doctor on the right floor.

McGirt happens to be a neurosurgeon, but he didn’t know Ivory’s injuries had anything to do with his specialty. When an operator connected him to a nurse who answered the phone, “Hello, neuro ICU,” his heart sank.

Any patient in a coma following a major brain injury is given a Glasgow Coma Score, ranging from 3 to 15. A patient with a GCS of 15 can move, speak, understand, and open their eyes normally; a patient with a GCS of 3 can’t move, talk, or breathe. Ivory’s GCS was 3.

“The two main predictors of outcome, meaning whether you will ever walk, talk, or feed yourself again, is the Glasgow Coma Score and the amount of herniation the brain has, [indicated by] the midline shift on a CAT scan,” McGirt explains. “Terrell had a very bad midline shift and the worst kind of score. He had every statistic going against him.”

The odds that someone in Ivory’s condition would wake up and be able to recover to a normal life, says McGirt, were no greater than 5 percent.

Laura McGirt, Matt McGirt ’94, Terrell Ivory, baby Trace, and Annie Marra, September 2019. (Photo courtesy of Jenny Savino, P’21, ’24)

Laura McGirt, Matt McGirt ’94, Terrell Ivory, baby Trace, and Annie Marra, September 2019. (Photo courtesy of Jenny Savino, P’21, ’24)

That, however, is what Ivory did. The first step, a few days after surgery, was breathing on his own. The next step came when Ivory woke up. He was disoriented and couldn’t remember how he’d gotten where he was, but he knew who he was and knew who the friends and family were who had gathered by his bedside. Ivory’s mother and brother had arrived by then and had gotten the chance to meet Ivory’s then-girlfriend, Annie, for the first time when she brought cookies to the hospital. (Annie visited almost daily and the Ivorys have gotten to know her even better since: Annie and Terrell got married in December 2020 and welcomed their first child in 2021, a son, Trace.)

Ivory stayed at Tufts for several weeks. He spent several more at an in-patient rehab facility in nearby Woburn before he could go home. In early September 2019, when Matt McGirt came to campus to drop off his daughter, he stopped by to check on Ivory’s progress. He was amazed by how well he was doing. Ivory’s skull flap was still off and he had friends and family helping him out at home, but he could perform most daily tasks and was on a best-case scenario recovery path.

Because his brain tissue was still exposed, Ivory had to wear a protective helmet when walking. Though it helped when his daughter added stickers, Ivory did not consider the helmet his most stylish accessory. Occasionally, he would conveniently forget to wear it when he walked around campus or checked in on some of his players. Mostly he just missed them, but he also worried he wasn’t there for them like he normally would be as they prepared for the season and connected with college coaches who stopped by throughout the fall.

“I felt guilty for putting them through that,” Ivory says, “and that helped motivate me to get better—so I could be there for my team every step of the way.”

Ivory worked hard at his rehab, though sometimes he pushed himself more than he should. Joel provided tough love when she ran into (read: caught) Ivory in the gym early that fall watching one of his players work out. She reminded him that the most important thing was for him to recover and stay healthy—and that the students would be just fine.

“She sent me this strongly worded email,” Ivory recalls, laughing. “It was so loving and so scary at the same time.”

COACH’S NEW APPROACH

By the time preseason tryouts rolled around in November, Ivory had had successful surgery to reattach his skull flap. His recovery continued to go well, and he was able to return to work coaching and in admissions. He couldn’t be as active a coach—jumping in drills and demonstrating technique—as he’d been before, but his limitations forced him to become a better verbal communicator. He leaned on team leaders like Dallion Johnson ’20, a captain, opening doors for the players to take ownership of the team.

“It was just great having him back,” says Johnson, who now plays basketball for Penn State. “It meant a lot, seeing how he pushed through so many challenges to come back to coaching.”

Ivory focused more on process—making sure players were giving high effort and constantly improving—than on results.

“Winning is really important to me. But when I was younger it was everything,” Ivory says. “Now, it’s like, if we do all these things and we play hard and we don’t win, as a coach, I’m good with that. If we win against a team that is not good, but we don’t play hard—that’s going to upset me.”

Ivory’s main message in his comeback 2019–2020 season was about overcoming adversity. He wanted his players to see his return as evidence that their own hard work would always bear results. The season started slow, with injuries hampering the team, but ultimately produced the most successful campaign and first playoff win of Ivory’s tenure.

In the last game of the regular season, Ivory got one more opportunity to hammer home his message. It was Andover vs. Exeter, at the Borden Gym. Andover got down early but tied it up when Johnson hit a buzzer-beater at the end of regulation to send the game into overtime. He did it again at the end of the first overtime period, but the game ended in a double-overtime heartbreak when a defensive mistake gave Exeter an easy last-second layup for the win.

It was hard not to feel devastated as visiting fans stormed Big Blue’s home court in a sea of red. Ivory, though, knew he had to keep his team focused. They were almost certainly going to make the playoffs; the only question was seeding and opponent. Ivory pondered how he’d motivate his players and help them get over the loss quickly while he waited for the standings to come out. When they did, the answer was obvious. Andover was getting a rematch with Exeter in the first round.

“I didn’t need to do anything,” Ivory says. “I simply told them we’re playing Exeter again.”

On game day, as Ivory watched his players in the layup line ahead of the playoff rematch, he had a sense that this game would be different.

“It was almost unfair to Exeter,” he says, “because we didn’t miss a shot.”

Andover won 73–63, the conclusion to a year that carried a special meaning for a team that hadn’t always been sure they’d get to have their coach by their side throughout.

“I understand on a deeper level that how we deal with adversity is important for success in life,” says Ivory. “A strong support system, like Andover’s, and teaching our students, athletes, and each other an approach that views obstacles as a critical part of success, helps develop the determination and ability to persevere through difficult times.”

Nora Princiotti ’12 is a staff writer at The Ringer, where she covers the NFL and occasionally Taylor Swift. You can hear her on The Ringer NFL Show and follow her on Twitter and Instagram @noraprinciotti.

Top photo by Lex Weaver

Other Stories

They’re simple and flexible. And increasingly, Andover investors are utilizing them to strengthen what they love at PA.

Skills for the future will require a critical balance of intellectual dexterity and technical expertise