December 16, 2021

Lost & Found

Pieces of a 68-year-old family mystery come together in Andover's archivesby David Perry

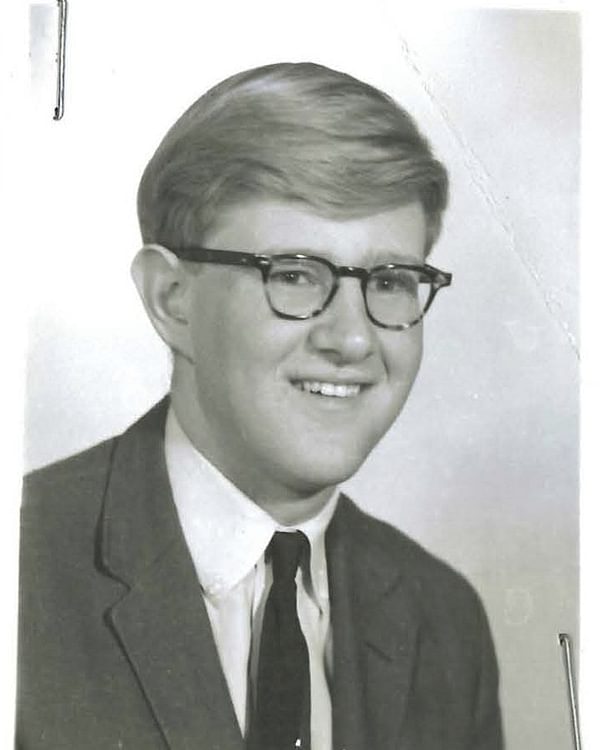

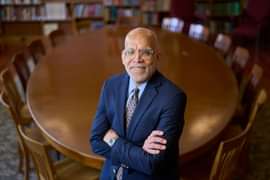

In the decade since she became director of Archives and Special Collections, Paige Roberts has received more than 2,500 research requests. Some simple, others complex. Students, faculty, staff, alumni, and scholars from far and wide. She can put a face to very few. Bill Damon ’63 is one of them.

In 2013, late on the Friday afternoon before his 50th Reunion, Damon walked into the archives’ offices. “I’m looking for some information about my father,” he told Roberts. Then he explained why.

“When I heard his story, it totally blew me away,” she says.

And so began Damon’s journey to know the father he never met, which is chronicled in his acclaimed new book, A Round of Golf with My Father: The New Psychology of Exploring Your Past to Make Peace with Your Present (Templeton Press)

Damon, a leading scholar on human development and a professor of education at Stanford University, where he serves as director of the Stanford Center on Adolescence, began his search nearly a decade ago, in his 60s—almost two decades after his dad, Philip Damon, had died.

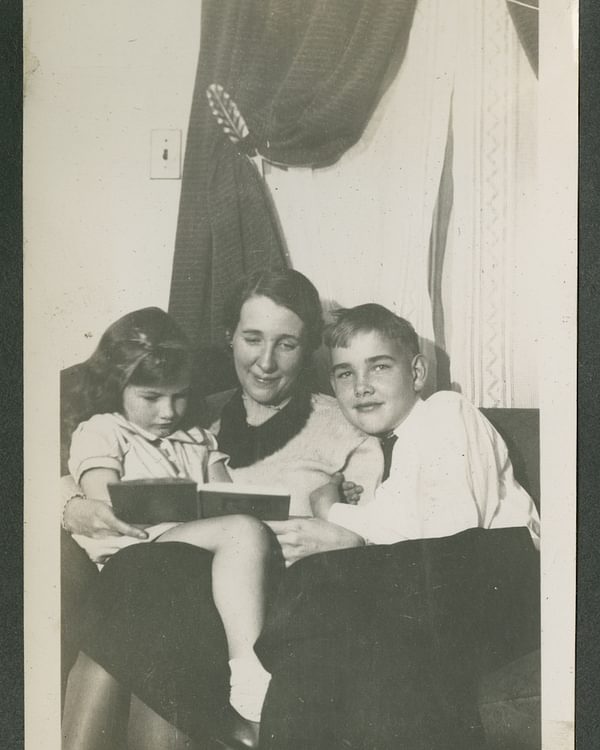

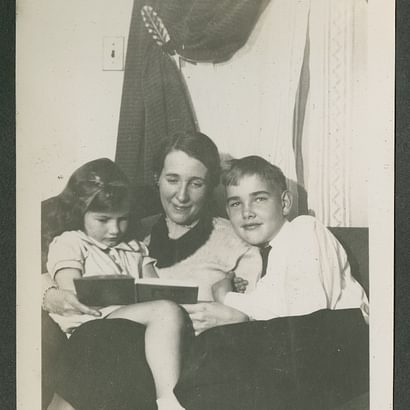

In winter 1944, Philip came home on leave from the war and married Helen Meyers. Then he returned to Europe to resume the fight. Helen’s only child, Bill, arrived nine months later. Philip never returned.

Until he was in college, Damon thought his father died in World War II, as his mother had implied. Then one day Helen dropped the truth on him—mentioning she would like to share the $100 a month Bill’s father had been sending her for all those years. Feeling ambushed by the news, Damon declined the money and decided against addressing the revelation with his mother.

In an instant, his father went from dead to deadbeat, he thought. Why stir that pot with her now? And he never did.

Memory is not like a photograph, meaning that a lot of the memories we have are not exactly right.

”The Call That Changed Everything

Are you the kind of person who’s afraid to look behind a closed door? Damon found himself having to answer that question when his daughter, Maria ’95, called in 2011.

“Dad, I’m not sure I should be telling you this,” said a hesitant Maria. “I found a lot of information on your father.”

Maria had been curious about her grandfather. In googling him, she discovered a small trove of information in an oral history within the records of the United States Information Agency (USIA).

“I was intrigued,” Damon says. “Because at that point, I was already a stable person with a family of my own. Earlier in my life, I wasn’t sure I wanted to identify this guy.”

Maria sent him the link. “And it just floored me,” Damon recalls. “It had everything in it. One thing after another. It was unbelievable.”

It turns out his father had attended both Phillips Academy and Harvard, a path Damon had unknowingly followed. The details of the story were, for decades, securely locked away in the Academy’s archives.

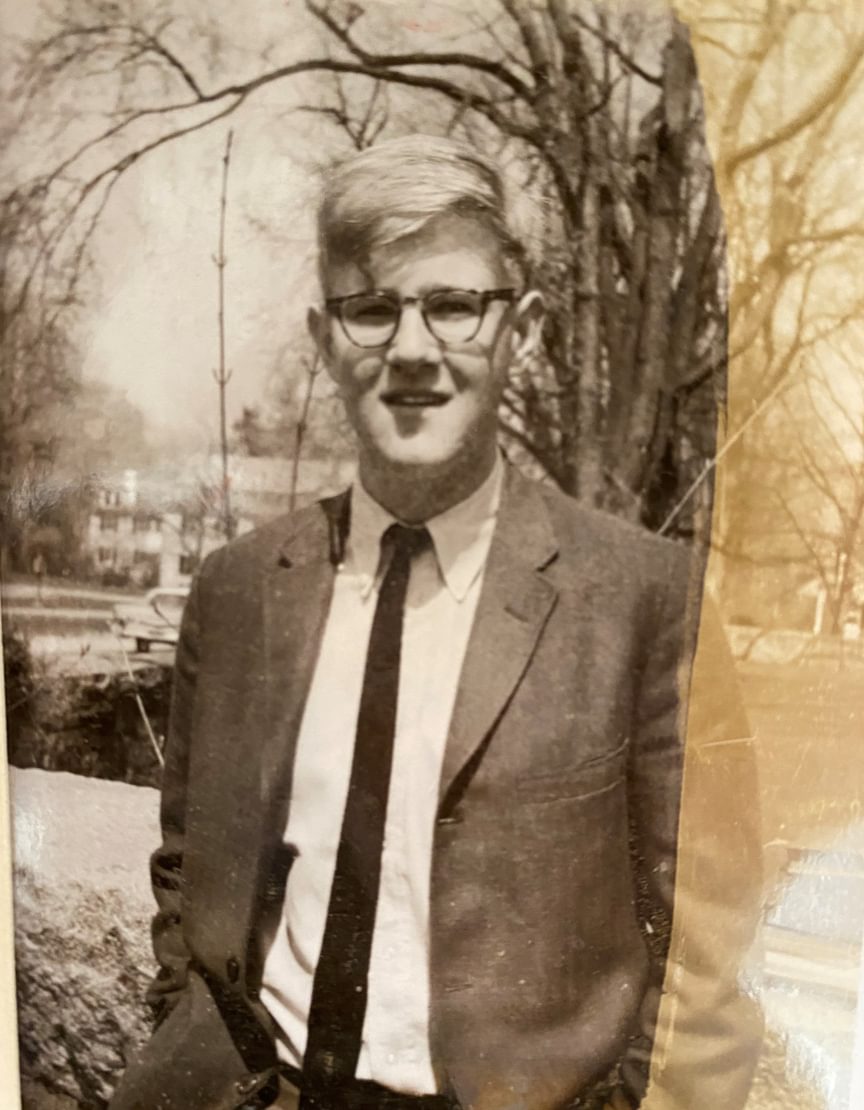

Phil Damon finished neither school, barely making it through his third year at Andover before being dismissed. He partied, was described as lazy, girl-crazy, and a troublemaker, and earned a series of written admonishments. Despite this, he was admitted to Harvard in 1941, but left the following year to volunteer in the Army. There, he found purpose and even moral courage, testifying at a war crimes trial following the war. He also worked for the USIA, spreading word of the benefits of democracy. Eventually, he married a French ballerina and started a second family, never returning to the first. And, like his own father, Phil Damon spent his final years in the throes of multiple sclerosis.

But of all the revelations, one in particular struck Damon—the description of his father as a “great golfer.”

A Round of Golf with My Father follows Damon’s quest to slay his buried regrets, conquer misconceptions, and answer long-dormant questions about his father. Calling upon a method developed by psychiatrist Robert Butler, Damon conducted a “life review” to examine his past through memory, documentation, and interviews. The process involves looking back on the highs and lows of one’s life, then squaring them against fact. It is a reckoning.

“Memory,” says Damon, “is not like a photograph, meaning that a lot of the memories we have are not exactly right. For example, I thought of myself as being shy and very intimidated by my peers in school. They were better athletes, smarter, harder working, the cool kids. But in the archives I discovered that several of my teachers wrote that I was outgoing, friendly, gregarious, well-liked. I couldn’t believe it, and it was helpful for me to see that.”

Research for the book took five years. Damon interviewed his father’s relatives, other relatives, and his newfound half-sisters, and raided archives from Andover to London.

The book culminates with Damon grabbing an old, worn golf bag his father once used and heading to the Pittsfield (Mass.) Country Club. The vintage golf bag, sent to Damon by a cousin, contained a scorecard Phil Damon filled out while playing the same course when he was 12. And on a gorgeous spring day, Damon joyously played 18 holes against the score card of his pre-teen father. And he lost.

But he also won. The life review liberated him from ignorance and anger. He forgave his father and found in the man several respectable traits.

“I came away with a couple of life lessons,” he says. “One is that you pretty much have to have conversations with people in your life before it’s too late. I didn’t get to do that with my mother. You need to clean up the mysteries in your life.”

Looking Back With Fresh Eyes

Roberts was ready when Damon appeared again in her office at the Oliver Wendell Holmes Library.

For all the historical content she oversees—managing the special collections of 7,000 books and the archives of all things official for Phillips Academy and Abbot Academy—Damon’s book impressed her.

It was Roberts who led Damon to folders about his father’s history at the school. Damon discovered notes on his father from an English teacher he also had two decades later, Hart Day Leavitt.

“I was amazed to find that and wondered, could he have ever put together that we were father and son? He never said anything if he had.” Sadly, Leavitt was gone by the time Damon wanted to ask.

Stories about our past are always a mixed bag of memories. Steeped in a stew of facts, experiences, nostalgia, and hearsay. While putting his own past under a magnifying glass, Damon was able to fill in the holes on an absentee parent—and found himself better understanding the parent who stayed with him for the long haul.

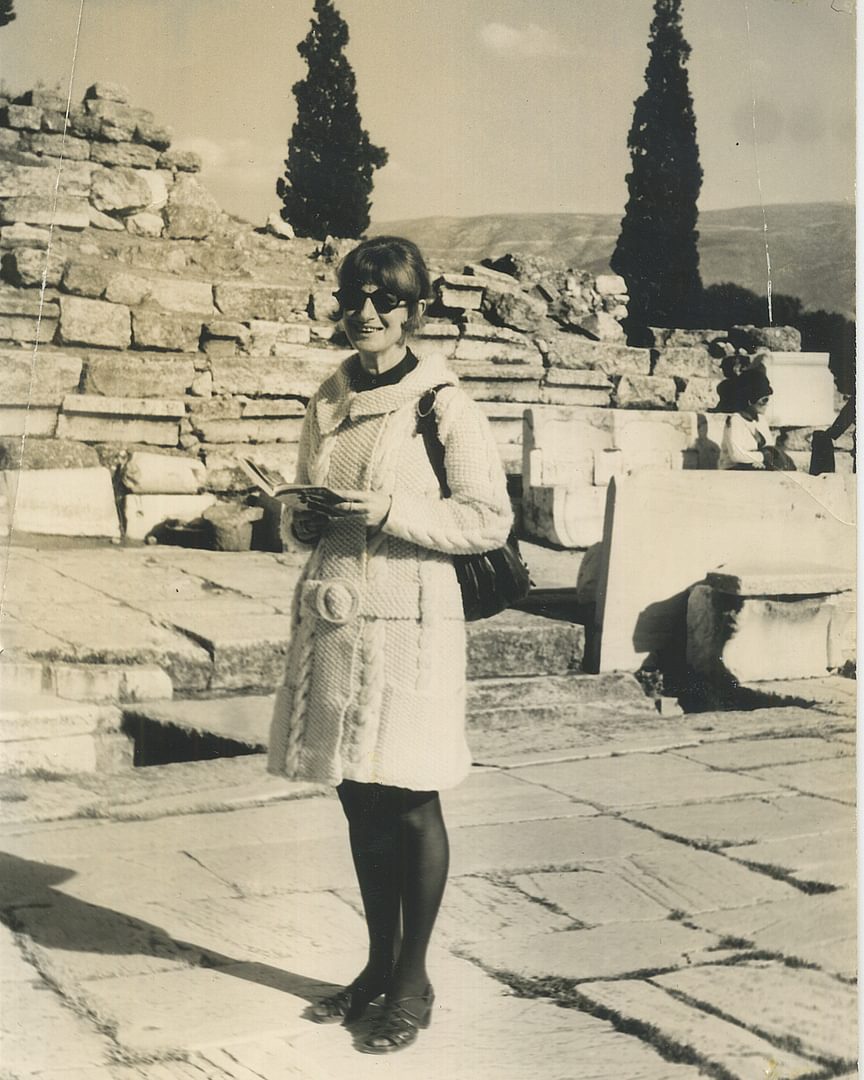

“My mother was obviously a very strong woman, very smart,” Damon says. “She was dealt a huge blow by my father not returning. And for three or four years, she just didn’t know if he wasn’t returning. She would still visit his parents. When she finally found out, it was devastating for her. But she did bounce back.”

Hard-working, full of love, and fueled by ambition, Helen (Meyers) Damon persevered.

“She had a career in the 1950s, which was not very common for women in those days,” says Damon. “And it was in advertising, which was a real live version of Mad Men.” Despite her hard work, she made considerably less than her male co-workers. But failing wasn’t an option.

In the ’60s, Helen designed shoes that were sold in some high-end boutiques around Cambridge and Boston. She was successful enough that Damon noticed the shoes worn by a girl he was dating were among those designed by his mother.

“She was a good mother and always made sure I had opportunities,” Damon says. “If my father had come home, maybe she would have lived out her days without having a chance to develop her love of fashion into a creative and fulfilling career.” Helen died in 2006. A retired entrepreneur and artist, she lived happily in a house she purchased by the sea in Maine.

In his search for himself, Damon found what he was looking for. Now at peace with his past, he also benefits from having gained an extended family. His two half-sisters live in Thailand, and he treasures their relationship.

“I’m hoping that through my example, trying to understand one’s past more clearly, I can help others do the same,” Damon says. “The present and future are important, but trying to obliterate the past and denying resentment and regret is a losing proposition.”

David Perry has covered news and feature stories in Massachusetts cities and towns for more than four decades. An award-winning features writer, he is also a Grammy-nominated artist for Best Album Notes for The Jack Kerouac Collection.