November 13, 2020

Reality check

Preserving the truth in an age of disinformationby Rita Savard

We live in a time of political fury and deepening cultural divides. In the era of 24/7 digital news, when anyone can immediately publish and reach a worldwide audience, the line between fact and fiction is increasingly blurred.

A group of powerful people intentionally planned the COVID-19 outbreak. Dark-clad thugs on planes are traveling around the U.S. intent on inciting unrest. Millions of mail-in ballots will be printed and sent in by foreign countries to rig the presidential election. Bizarre conspiracy theories such as these are just a few examples of “fake news,” which has sprouted and grown to tremendous proportions online this year.

Misinformation, spin, lies, and deceit have, of course, been around forever. But in the digital universe, a unique marriage between social media algorithms, advertising systems, the motivation of quick cash, and a hyper-partisan U.S. government has had dangerous real-life consequences.

From U.S. elections to the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement, alumni journalists and policy strategists say that navigating, identifying, and seeing through disinformation in a bewildering media environment relies heavily now on how much we, the social media users—along with big tech companies, public education systems, lawmakers, and credible news organizations—nurture and develop media literacy so that we can consume news with a critical eye.

“Some days it feels like democracy is drowning in fake news,” says Dan Schwerin ’00, a political strategist who co-founded Evergreen Strategy Group, which provides speechwriting, strategic advice, and communication services to companies facing diverse and complex policy challenges. Schwerin was also Hillary Clinton’s chief speech writer during her 2016 presidential bid and principal collaborator on Clinton’s two best-selling memoirs, Hard Choices (2014) and What Happened (2017).

Politics can be a painful business. For Schwerin, 2016 was an especially hard-hitting example of how far disinformation can go to inspire real-world violence.

“Certainly, we knew that during a campaign there would be misinformation,” he says. “There had been misinformation and lies told about Hillary Clinton for 30 years, but the moment that fake news became a starkly real problem for me wasn’t until a few weeks after the election.”

In early November 2016, when Clinton campaign manager John Podesta’s email was hacked and the messages were published on Wikileaks, one of the emails (according to the New York Times) was between Podesta and James Alefantis, the owner of D.C. pizzeria Comet Ping Pong. The message discussed Alefantis hosting a possible fundraiser for Clinton.

Users of the website 4Chan began speculating about the links between Comet Ping Pong and the Democratic Party, with one particularly dark conjecture bubbling to the surface: the pizzeria is the headquarters of a child-trafficking ring led by Clinton and Podesta.

As outrageous as it sounds, the conspiracy theory took root on far-right conservative websites and misinformation was kicked around 4Chan until someone posted a long document with “evidence” to a now-banned alt-right section of Reddit just days before the U.S. election. The alt right is a fringe group of far-right extremists—comprising white supremacists and racists—who share their views and various forms of propaganda online.

On Dec. 4, 2016, Edgar Maddison Welch, a father of two from Salisbury, North Carolina, took it upon himself to police a rumor he believed to be true. After reading online that Clinton was allegedly abducting children for human trafficking through the D.C. pizzeria, the then–28-year-old Welch—purportedly on a rescue mission—armed himself with an AR-15 semiautomatic rifle, a .38 handgun, and a folding knife and drove a few hundred miles north to Comet Ping Pong, a 120-seat kid-friendly pizza place with ping pong tables and craft rooms.

“I knew the restaurant well,” Schwerin adds. “It wasn’t far from my house and was a place where I ate many times.”

Dan Schwerin ’00

Dan Schwerin ’00

Welch didn’t find any captive children at the pizzeria. When he made his way into the kitchen and shot open a locked door, he discovered only cooking supplies. Despite the rumors on 4Chan and far-right news outlets like Info-Wars, the pizzeria had no basement.

“When he got there and realized that there was no basement, that should have been the tip-off that he had been duped,” Schwerin says. The incident, now widely known as “Pizzagate,” remains a vivid example of how fast falsehoods can spread, how some people are quick to believe them, and how they can lead to dangerous consequences.

“If you track that conspiracy theory and the kinds of outlets that promoted it, and how it led to real-world violence—that, for me, was a real shock,” Schwerin adds.

We exist in a world of extreme polarization, and efforts to educate people about how to use digital media well and savvily is a very tough assignment—because even when presented with evidence and hard facts, some minds can’t be changed because they simply don’t want to.

”“Falsehood flies, and the truth comes limping after it,” wrote satirist Jonathan Swift. Fast-forward to more than three centuries later when social media platforms are the primary vehicle for delivering information to millions at a pace that’s difficult to manage and monitor.

“We exist in a world of extreme polarization, and efforts to educate people about how to use digital media well and savvily is a very tough assignment—because even when presented with evidence and hard facts, some minds can’t be changed because they simply don’t want to,” says Alexander Stille ’74, author, journalist, and professor of international journalism at Columbia Journalism School. “But some room for optimism does lie in the behavior of private companies.”

In 2017, dictionary.com added a definition for the term fake news. The entry reads: false news stories, often of a sensational nature, created to be widely shared online for the purpose of generating ad revenue via web traffic or discrediting a public figure, political movement, company, etc.

Several data-based studies in recent years show that false news travels farther, deeper, and faster than true stories on social media, and by a substantial margin.

To learn more about how and why false news spreads, researchers at MIT tracked roughly 126,000 Twitter “cascades” (unbroken retweet chains of news stories) that were tweeted over 4.5 million times by about 3 million people, from 2006 to 2017. Politics comprised the biggest news category, with about 45,000 cascades, followed by urban legends, business, terrorism, science, entertainment, and natural disasters. The spread of false stories was more pronounced for political news than for any other category.

But while social media giants, including Twitter, Facebook, and Google are publicly announcing ways to combat fake news in 2020, they are simultaneously benefiting from associated ad revenue tied to falsehoods that go viral.

Engagement, not content—good or bad, true or false—is what generates internet revenues and profit. Our posting, sharing, commenting, liking, and tweeting produces behavioral and demographic data that is then packaged and sold, repackaged and sold.

” Soraya Chemaly ’84

Soraya Chemaly ’84

Soraya Chemaly ’84, an award-winning author, activist, and executive director of The Representation Project (a nonprofit harnessing film to create a world free of limiting stereotypes), says fake news isn’t just dangerous because it distorts public understanding but—as in the case of Pizzagate—it also “is frequently implicated in targeted online harassment and threats.”

The co-author of the investigative journalism article, “The Risk Makers—Viral hate, election interference, and hacked accounts: inside the tech industry’s decades-long failure to reckon with risk,” Chemaly points out that when tackling issues of fake news, media often center around the nature of the truth, the responsibilities of social media companies to the public good, and the question of why people believe outrageous and unverified claims. But very little gets said about a critical factor in the spread of fake news and harassment—that they are powerful drivers of profit.

“Engagement, not content—good or bad, true or false—is what generates internet revenues and profit,” Chemaly says. “Our posting, sharing, commenting, liking, and tweeting produces behavioral and demographic data that is then packaged and sold, repackaged and sold.”

This business model played out in more than 3,500 Facebook ads placed by the Kremlin-linked Internet Research Agency (IRA) around the 2016 election, which targeted conservatives and liberals alike.

Fear and anger drives clicks. On Feb. 16, 2018, Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III indicted 13 Russian individuals and three Russian organizations for engaging in operations to interfere with the U.S. political and electoral process, including the 2016 presidential election. This was a significant step toward exposing a social media campaign and holding those accountable responsible for the attack. The indictment spells out in exhaustive detail the breadth and systematic nature of the conspiracy, dating back to 2014, as well as the multiple ways in which Russian actors misused online platforms to carry out clandestine operations.

Throughout the indictment, Mueller lays out important facts about the activities of the IRA—a troll farm in St. Petersburg, Russia, which flooded Facebook with fake content in the run-up to the 2016 election. According to U.S. government documents, the IRA created fake news personas on social media and set up fake pages and posts using targeted advertising to “sow discord” among U.S. residents.

Users flipping through their feeds that fall faced a minefield of incendiary ads, pitting Blacks against police, Southern whites against immigrants, gun owners against Obama supporters, and the LGBTQ+ community against the conservative right—all coming from the same source thousands of miles away.

“Until the business model is directly dealt with, until the mechanisms that implicate fake news and disinformation are considered—until we demonetize disinformation to ensure that fake news cannot make money from ads—nothing is going to get solved,” Chemaly says.

As a result of racial injustices, Americans have taken to the streets across the country this year to let their voices be heard. The Black Lives Matter movement—which became a hashtag in summer 2013 when Oakland, California, labor organizer Alicia Garza responded on her Facebook page to the acquittal of George Zimmerman, the man who gunned down 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black high school student—has mounted some of the most potent civil rights activism since the ’60s.

Any large social movement is shaped by the technology available in the moment. Today’s anti-racism outcry, along with the COVID-19 pandemic, has been ripe for online trolls and others seeking to exploit tensions.

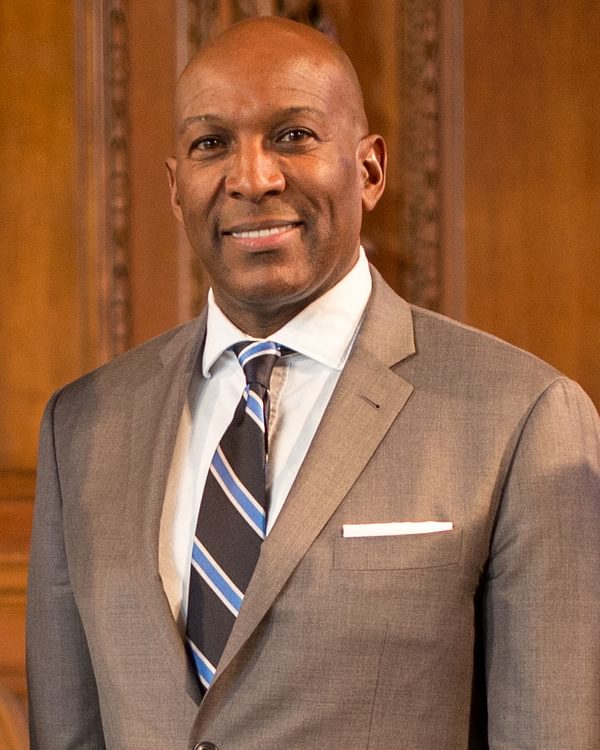

George Bundy Smith Jr. ’83, a veteran journalist and news anchor for WKOW ABC in Madison, Wisconsin, was on the ground covering protests when they began at the end of May.

“From what I observed, the protests drew hundreds of people from all different races and lots of young people,” Smith recalls. “It was encouraging to see that kind of unity in a predominately peaceful way. There are civil society organizations working to build positive movements for the long haul, but they also have to work to counter misinformation on the issues they care about.”

George Bundy Smith Jr. ’83

George Bundy Smith Jr. ’83

The protests in Madison, he adds, were not immune to vandals. While the majority of protests were peaceful, over the course of a few nights, businesses had windows broken and some were looted. White people and people of color were responsible for the destruction of property. But over the course of the summer a barrage of fictional narratives, from missing person accounts to acts of violence—even a false claim that a news organization used a clip from the movie World War Z to illustrate chaos in the streets—flooded social media platforms.

Online disinformation campaigns stating that protests were being inflamed by Antifa (an anti-fascist action and left-wing political movement) quickly traveled up the chain from imposter Twitter accounts to the right-wing media ecosystem and called for an armed response. This fake news, coupled with widespread racism, is believed to be why armed groups of white vigilantes are taking to the streets in different cities and towns.

In September, FBI Director Christopher Wray ’85 warned the House Committee on Homeland Security that when disinformation mobilizes, it endangers the public. “Racially motivated violent extremism,” mostly from white supremacist groups, Wray says, has made up a majority of domestic terrorism threats this year.

“I want to be optimistic about change,” Smith says, “but it’s difficult when we are dealing with the same issues that were there when I was a kid—police violence and accountability.”

Smith, who is Black, says he has been pulled over by police 20-plus times throughout his life.

“I have a routine now,” he says. “Interior lights on, ignition off, I put my keys on the dashboard, I’ve got my driver’s license ready so I don’t have to reach for anything, hands on the steering wheel, windows down—I do it every time and although I haven’t had a really unpleasant traffic stop, I definitely think I’ve been pulled over for questionable reasons.

“I have Black Andover friends—lawyers, brokers, professional hard-working citizens—who have also had these experiences. Dealing with this issue still, in 2020, is disturbing,” says Smith. “I like to think we’re at a turning point now, but there is clearly much work ahead.”

Cutting through the noise of fake news and half-truths, public pressure, Smith adds, has played a significant role in prompting officials to take action.

“The initial press release from the Minneapolis Police Department was vague and made no mention of an officer kneeling on George Floyd’s neck,” Smith says. “Fortunately, there was a video that told a more complete story. In Kenosha, when Jacob Blake was shot seven times, there was no mention of that in the initial press release. A viral video, however, forced officials to release more information. What if, in these instances, there was no video? Would we have ever learned the truth?

“Transparency is a big deal, and you have to hold officials accountable, whether it’s the police or the president.”

The following sentence is not fake news: Media literacy works, and it will make consumers smarter and more discerning when it comes to following and detecting credible news sources—but it will take a united front.

“Whenever you have a transformative technology, there are going to be people who use it in unexpected ways” says Nick Thompson ’93, editor-in-chief of WIRED magazine, which focuses on how emerging technologies affect culture, the economy, and politics. “In the beginning, I think the creators of [social platforms] were looking at all the ways in which the tech could bring people together and not really thinking about how a computer code could be used against democracy. There was a lack of appreciation for the dark side.”

The Facebook algorithm, for example, is how Facebook decides which posts users see and in what order every time they check their newsfeeds. In January 2018, Facebook co-founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced newsfeed changes that prioritize “posts that spark conversations and meaningful interactions.” The algorithm was set to prioritize posts that earned a lot of high-value engagement.

A year later, a study conducted by the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard found that while engagement had increased, the algorithm changes also increased divisiveness and outrage, as it tended to promote posts that got people riled up. Simultaneously, the algorithm ended up rewarding fringe content (aka fake news) from unreliable sources that knew how to game the system.

We play a significant part in training the system, so it’s not just what we do in the moment that matters, but how we are shaping the system as a whole.

” Nick Thompson ’93

Nick Thompson ’93

While the Facebook algorithm will probably always be a work in progress, Thompson believes that “if Facebook could wave a magic wand and get rid of fake news, it absolutely would.”

“The reputation of damage to the platform outweighs the benefit of any revenue they’re bringing in,” he says. “But it’s a complex fix, because while social media companies have to take responsibility at the developmental level, we have to remember the algorithm is also responding to what we are clicking on every day—our actions determine where the algorithm leads us.

“There should definitely be responsibility for the tech companies to have consequences for what they’re publishing, but we, as users of the tech, have to have a new level of self-awareness,” says Thompson. “We play a significant part in training the system, so it’s not just what we do in the moment that matters, but how we are shaping the system as a whole.”

This past summer, Twitter began adding fact-checking labels to tweets, including some originating from President Trump. It also suspended thousands of accounts associated with QAnon, a once far-right fringe group that went mainstream through social networking. QAnon’s sprawling internet conspiracy theory operates under the belief the world is run by a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles who are plotting against Trump while operating a global child sex-trafficking ring—a story many believe gained momentum after the Pizzagate conspiracy.

In early October, Facebook followed Twitter’s lead and announced that it would ban all QAnon accounts from its platforms, labeling it a “militarized social movement.” On the heels of that decision, Facebook also banned content about Holocaust denial.

In the past Zuckerberg said that he would not censor content from politicians and other leading figures for truthfulness. But in an Oct. 12 Facebook post, Zuckerberg said his thinking had “evolved” because of data showing an increase in anti-Semitic violence.

In the end, says journalism professor Stille, the battle against fake news will require a united front that includes social media users, government, industry, and journalists.

“As a journalist who has worked within the constraints of American libel law, one of the things that is strange to me is there are clear rules that you cannot publish things that are false and you cannot publish with reckless disregard or malice yet, unfortunately, on social media those same standards aren’t applied.

“Free speech is vital to democracy but when misinformation is fiercely pushed, defended, and sold as truth, democracy is at risk. Somebody has to exercise some degree of control and responsibility or we’re just looking at a Hobbesian war against all information.”

Categories: Magazine

Other Stories

Sarah Sherman ’04 on NASA's groundbreaking tech that will help humankind reach new heights in space