February 09, 2018

Taking the rains

Hadley Soutter Arnold ’82, P’19, is tackling the western U.S.’s water crisisby Rita Savard

We take water for granted. And why shouldn’t we? We turn on the tap and out it comes. But in the parched American West, where punishing drought, raging wildfires, and other effects of climate change are draining major water supplies, one thing is clear: The way we access water needs to change.

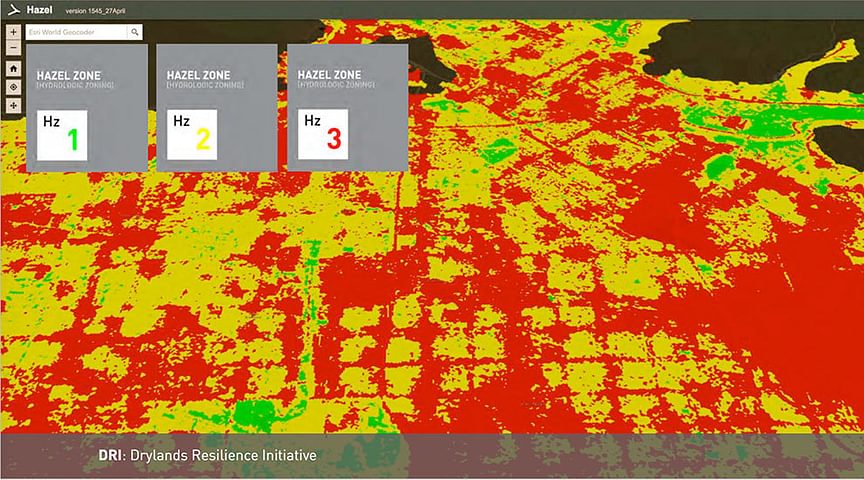

Hadley Soutter Arnold ’82 has created a solution, and its name is Hazel—for the wood used in traditional divining rods. A digital mapping tool, Hazel integrates aquifer, pollution, and land-use data to help designers and engineers develop healthy local water supplies from harvested rainwater. “If we can capture rain strategically, even infrequent rain,” explains Arnold, “we can meet the needs of millions in Los Angeles through low-cost, low-tech tweaks to city surfaces.”

LA is a city on the edge of a desert. Its roughly 4 million people depend on water imported from the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountains—also the water lifeline for millions of other Californians as well as the state’s agricultural industry. A dearth of mountain snow in recent years, a direct result of climate change, prompted sweeping water use restrictions in 2015. Yet the city still relies on the purchase of dwindling snowpack to quench its thirst while billions of gallons of free local stormwater gets flushed into the Pacific Ocean every time it rains.

Enter Hazel. Using geospatial data, Hazel exposes a landscape’s hidden hydrology. By peering into LA, for example, users can see precisely, street by street, lot by lot, where stormwater can be captured, stored, and treated to offset the city’s dependence on piped-in water.

“When we use Hazel to look deeper into LA, we see tens of thousands of strategic opportunities to build water supply,” Arnold says. “Hazel uncovers that potential and puts it into our hands.”

With this kind of water-smart tech, property owners, developers, designers, and planners can make rapid, informed decisions for creating greener, more water-sustainable buildings, towns, and cities.

Cofounder of the LA-based Arid Lands Institute—a research and development center dedicated to building new tools for water-smart planning and design—Arnold grew up in Rhode Island, where her family encouraged independent thinking and a love of the arts, community, and the outdoors. Arnold says Andover built on that foundation with its culture of creative questioning. In 1981, she helped usher in a new era at Andover when she became the first female elected class president.

We wrestled with hard questions at Andover,” says Arnold, whose daughter, Josie ’19, also chose Andover to challenge herself. “That habit of finding your voice through continual questioning: it’s the Ground Zero for all creative leadership.

”Arnold met her husband, Peter, while both were studying architecture in graduate school. He is the other half of Arid Lands Institute. Daunted by the water supply challenges facing Los Angeles, the couple began looking for fresh approaches to solve the problem. Not all solutions are technical. The Arnolds also look to history and traditional communities like New Mexico’s acequias—small-scale water cooperatives—to study alternative models of sharing scarce desert water and designing public spaces in drylands.

In LA, most rainwater ends up in storm channels that funnel into the ocean. The way Arnold sees it, every gallon of “free” rainwater equates to a gallon of drinking water that has to be purchased at a much higher cost. So how would the future look if Hazel’s smart tech was used to turn buildings, towns, and cities into virtual sponges using trees, drought-resistant plants, underground aquifers, rooftop cisterns, water-themed public artwork, and much more, all aimed at conserving and reimagining water?

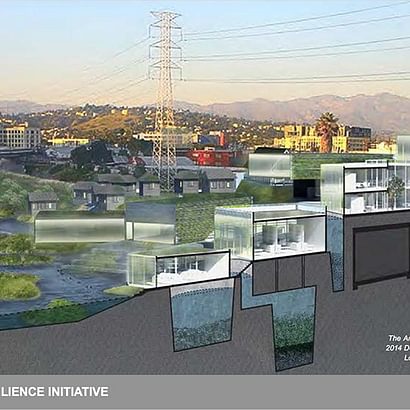

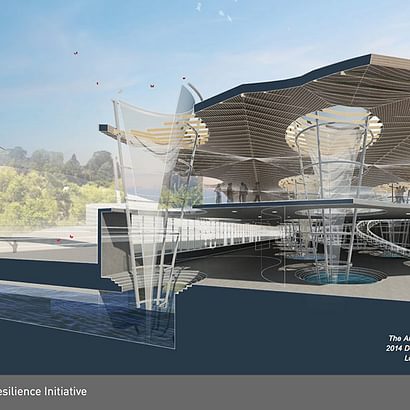

In 2014, 120 teams of architects from around the world signed up for a design challenge to show the possibilities. The challenge was put forth by global architectural and design firm Perkins+Will, a company led by Arnold’s friend and PA classmate Phil Harrison ’82. The results were eye-opening.

A hypothetical new home for Arid Lands Institute on the banks of the Los Angeles River was illustrated in myriad ways, purposefully designed to collect every drop of water. While the challenge provided only a glimpse of what could be, it proved that smart-use water design could not only make communities more sustainable, but also more connected, meaningful, and inspiring.

“The Perkins+Will design experiment spurred us to continue to work on developing the tool, which we now recognize has applications well beyond LA,” Arnold says.

But Hazel can only be useful if implemented, and most towns and cities, Arnold says, are slow to change. Those eager to consider new green-tech solutions are often hindered by political boundaries and limited budgets. That’s why Arid Lands Institute is focusing on relationships with designers and engineers, hoping these professionals will bring Hazel to water-stressed urban centers worldwide. The goal is to bring Hazel to market this year.

“Designers and engineers have an immense opportunity to work with a changing hydrologic cycle and bring water back to the center of community design,” Arnold says. “We’re happy to support them. Because if we don’t have water, we don’t have a home.”