October 24, 2013

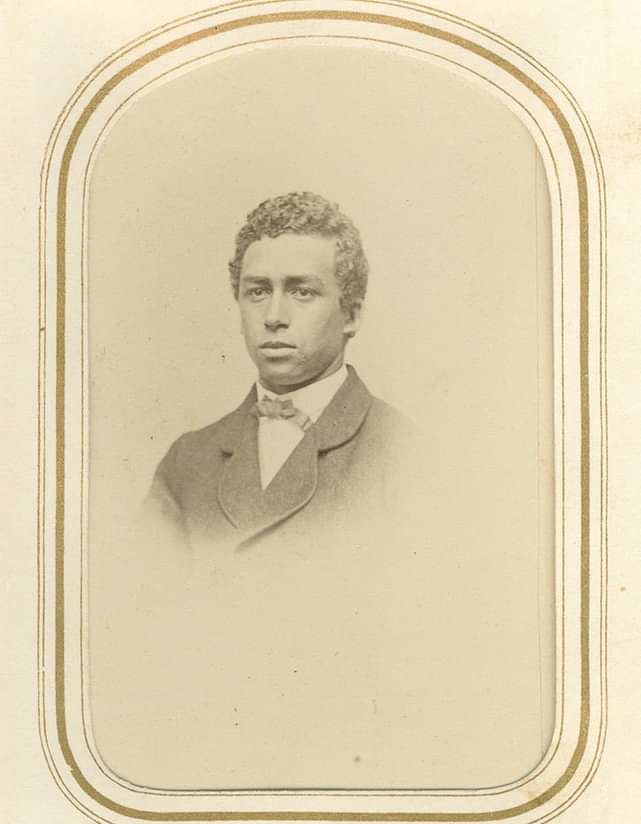

Richard T. Greener at Andover

Discovery revives forgotten legacy of 19th-century black intellectualby Amy Morris

To this day, no one knows how a steamer trunk stuffed with documents, photos and books belonging to Andover alumnus Richard T. Greener landed in the attic of an abandoned house on Chicago’s South Side, but its discovery in 2009 has revived the largely obscured legacy of one of the 19th century’s leading black intellectuals.

The discovery has caused a stir among many scholars who thought Greener’s papers had long been destroyed; Harvard’s Henry Louis Gates, Jr. said he got “gooseflesh” when he learned about it. Libraries, museums and universities are eager to acquire certain Greener documents (the University of South Carolina recently paid $52,000 for some). And last week, the man who discovered the papers threatened to set them on fire, after he received, what he believed to be, an insultingly low offer from Harvard to buy them. The news media paid attention, too.

Greener graduated from Andover in 1865 and Harvard in 1870, then quickly became a member of what W.E.B. Dubois called the “talented tenth,” the black “aristocracy of character and talent” whose mission, as Dubois saw it, was to help empower black Americans in the wake of the Civil War. Greener’s personal acquaintances (some were friends, some were adversaries, all were admirers) included Dubois, Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison, John Brown, Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington and Ulysses S. Grant.

Still, before the discovery of his papers, Greener’s legacy had been reduced to a footnote: Harvard College’s first black graduate. But because he spent much of his life in the public eye, his work as a prominent educator, diplomat, lawyer and intellectual was well-documented. Greener’s time at Andover, however, was given little notice.

Greener grew up in Boston, dropping out of school at the age of 14 to help support his single mother. Among his various jobs, he worked for a silversmith named Augustine E. Batchelder, who would become his benefactor, first supporting his two years at Oberlin College, and then his year at Andover.

Twenty-year-old Greener came to Andover as a senior—and the school’s only black student—in 1864. The nation was in the throes of the Civil War. And Andover was in the throes of principal Samuel Taylor: it was said that for “Uncle Sam,” each student was guilty until proven innocent, something Greener confirmed in a speech at his 50th reunion in 1915. He recalled the humiliation he endured on his first day of school.

“I was sitting feeling very meek in the back seat, to have my name shouted out before the entire 300— ’Greener!’ I was astounded, shocked. Again it was repeated—‘Greener, you may leave the room.’ I rose cautiously, put my books together with the utmost ease and comfort, straightened myself to a military gait and walked down the hall, bowed to Uncle Sam, went to the door, closed it carefully, and when I knew it was closed I shook my fist at him through the door.”

Later that day, Greener confronted “Uncle Sam” as they walked up a staircase.

“I said, ‘I was not conscious of having done anything and I don’t know why you sent me out.’ Another step up. He looked at me fiercely and said ’You were whispering, sir.’ Another step up. I said, ‘I was not whispering, sir.’ When he reached the top he said: ‘Well, sir, if you were not whispering your whole manner indicated levity.’"

But Greener, who remained a fiercely proud alumnus of Andover until his death in 1922, only had the highest praise for the dictatorial principal, later saying him,

"I have never had a teacher in literature, I have never had a book upon literary composition, that did me as much good as his criticisms on the Latin and Greek authors.”

During his year at Andover, Greener earned such respect among his peers and the faculty that he served as editor of the Philomathean Society’s literary magazine, The Mirror. The July 1865 edition bearing his name on the masthead features a front-page editorial mourning President Lincoln’s assassination that April.

Judging from his letters in later years to headmaster Cecil Bancroft, Greener’s memories of Andover were inextricably tied to the milestones of the Civil War. In 1886, he wrote, “It was at Andover in 1865—my own class year—that I heard of the ‘Fall of Richmond’ and dimly comprehended all that the event foreshadowed.” In another, dated April 10, 1891, he noted, “Twenty-six years ago, yesterday, at Andover, I heard of Appomattox, and comprehended what that victory portended for the whole country.”

The program for Andover’s 1865 commencement, then called the Exhibition, shows that Greener spoke on “Ancient Rome Modernized.” This may well have been the last speech Greener gave publicly in which his race went unmentioned. A month later, the Boston Journal reported that, among the speakers at an exhibition for Andover’s Philomathean Society was “Richard T. Greener of Boston (colored) who showed great depth of thought and much research in the manner in which he handled his subject—‘The Teachings of History.’”

Once he passed the Harvard entrance exam, Greener’s role as a black leader began to take root. As the nation pondered four years of carnage and embarked upon Reconstruction, Greener’s admission to Harvard became a symbol for what America could be. The periodical The Independent editorialized that, with Greener’s admission, Harvard had “taken its stand upon the principle of equal rights, irrespective of color.”

At Harvard, Greener twice won the prestigious Bowdoin Prize, prompting the Hartford Daily Courant to declare, “The news will curdle the blood in the veins of every Democrat of the old school who remembers ‘the Union as it was.’”

Greener later credited his Andover education for his success in college, writing to Bancroft that it was “because of the training of ‘Uncle Sam,’ and the practice in ‘Philo’ and ‘The Mirror’ I attribute my success at Harvard.”

Greener was not Andover’s first black student (Thomas B. Smith attended in 1838 and Samuel C. Watson in 1849), but, for a time, he was its most famous. Among his later achievements, he was the University of South Carolina’s first black professor (until the end of Reconstruction in 1876, when the university closed its doors to black students and faculty); he served as dean of Howard University’s School of Law; he was secretary of the Grant Monument Commission, and, as such, was largely responsible for the erection of the memorial on Riverside Drive in New York City; and he later served, under President McKinley, as the U.S. consul in Vladivostock, Russia during the Russo-Japanese War.

Throughout his career, he remained loyal to his alma mater. In 1886, he gave the school an engraved portrait of General Grant by William E. Marshall, writing “I take pride, in presenting to my Alma Mater—to whom I owe so much, this portrait of the man, who led our armies to victory, as a remembrance of a re-united and free country, and as a stimulus to future ‘Sons of Phillips,’ in duty and patriotism.”